as seen in the October 2020 release of Golf Inc. Magazine

Rightly or wrongly, the golf industry has long been measured against airlines and hotels when pundits seek to compare its overall strength and progress to other hospitality sectors. It’s a logical analogy, given that all three businesses employ service-oriented models that sell a product whose value is inextricably linked to time.

For companies in these spaces, once a tee times passes, a flight takes off or a room night turns to day, the revenue-generating power of the respective pieces of “inventory” perishes. If, by chance, they go unused or unfilled altogether, managers are left empty-handed, wondering what could have been done to recoup at least a fraction of that time’s worth.

In many ways, however, that’s where the similarities end.

Every airline and the vast majority of hotels utilize cloud-based dynamic pricing to continuously adjust rates up or down in real time until a flight departs or the clock strikes 12 on a room night. This ensures each company gets the maximum yield (i.e., profit) for every seat filled or head placed in a bed. Most commercial carriers further insulate themselves from lost revenue by requiring prepayment for flights and enforcing add-on fees for any changes once a reservation is confirmed.

Though the lodging sector remains slightly behind airlines in its payment practices, virtually all hoteliers ask for a credit card number to hold a room for a given night and will charge a penalty or the entire agreed-upon rate if the reservation is cancelled after a certain date. A growing number of properties are also mirroring airlines by implementing prepayment policies to deter last-minute cancellations and no-shows.

The golf industry’s revenue preservation policies, on the other hand, are essentially nonexistent.

A potential customer can go online or call the pro shop of most any public or semi-private course in the United States days or weeks in advance to book a tee time for an upcoming date—including premium weekend spots—for up to four players. The cost to the golfer to reserve those four slots and remove them from the course’s pool of potential revenue-producing inventory: nothing. The amount of money the club receives if that foursome cancels on the morning of the tee time or the golfers fail to show up altogether—nothing.

It doesn’t take a mathematician to calculate the impact that last-minute cancellations or unexpected no-shows can have on a course. Even the seemingly benign scenario in which only two players arrive to play when a foursome was booked can dramatically affect the bottom line.

For example, if those individual tee slots are priced at $50 each, the course will experience a $100 loss at best (in the event that two of four players show); at worst, it will incur a $200 negative hit. Multiply that by a few unused tee times per day, several each week, double-digit numbers monthly, and by year’s end the figure can be staggering, especially for facilities that already operate on razor-thin margins.

The question that bears asking is why don’t course owners and operators do something—honestly, anything—to better protect their most valuable asset?

They have access to the same technology that airlines and hotels use to tweak rates, collect prepayments, and enact cancellation policies, so why wouldn’t they follow suit?

Blame it on history.

A Tradition of Resistance

In the game and business of golf, progress has historically stalled where tradition and innovation intersect.

Take, for instance, the golf cart. Invented in the 1930s, this now-ubiquitous mode of on-course transportation wasn’t widely embraced until two decades later, when a number of pioneering clubs began to realize the revenue-generating potential that motorized vehicles afforded. Today, only a handful of golf facilities in the United States don’t have a fleet of carts on their ledger sheet.

Adoption of technology has proven equally sluggish inside pro shops.

Long after electronic tee sheets and point-of-sale (POS) systems were introduced, customer-facing personnel could still be found reserving tee times on paper and using cash registers to conduct other transactions. Most course operators now utilize computers and other digital tools to some degree in their operations; however, the industry as a whole remains years, if not decades, behind others in terms of technology acceptance and implementation.

Truth is, if you ask most course managers about altering any aspect of their business, chances are they’ll respond with some variation of “We don’t have the time or resources to do that,” “My customers wouldn’t like that or pay for it” or “We’ve always done things a certain way.”

Justified or not, they’re often paralyzed by fear of what might happen—or not—by disrupting the status quo, even if it means accepting the same outcomes (including those that are mediocre or worse) that they’ve achieved for years on end.

Accordingly, golfers continue enjoying the freedom to book, then cancel or fail to show up for, tee times whenever and wherever they want with no exchange of money or the threat of financial repercussions. On the opposite side of the counter, golf professionals and course operators are left scrambling to fill empty spots, recover lost revenue through creative cross-selling or marketing gimmicks, and answer oft-asked questions from higher-ups about why budgets for greens fees aren’t hitting their targets.

Trapped in a self-perpetuating cycle of change resistance, the game and business plod along.

At the Intersection—Again

As a new decade begins in earnest, tradition and innovation in the golf industry have once again converged. This time, the confluence was driven by the unlikeliest of catalysts: a global pandemic.

COVID-19 disrupted daily routines and traditional means of doing business in ways that most Americans never could have imagined. Golf, as a sport and an industry, enjoyed an uptick in popularity and rounds played during the first half of 2020, but neither the game nor the business escaped other challenges associated with the disease.

The men and women charged with running the nation’s more than 16,000 golf courses had to adjust their operations to comply with state and local mandates for social distancing and group gatherings, and take other precautions to prevent spread of the virus. A small number of course managers went on the offensive, using the disruptions created by COVID-19 as opportunities for select organizational transformation.

One of these agents of change was Dustin Volk, head professional of Valley View Golf Course in Layton, Utah.

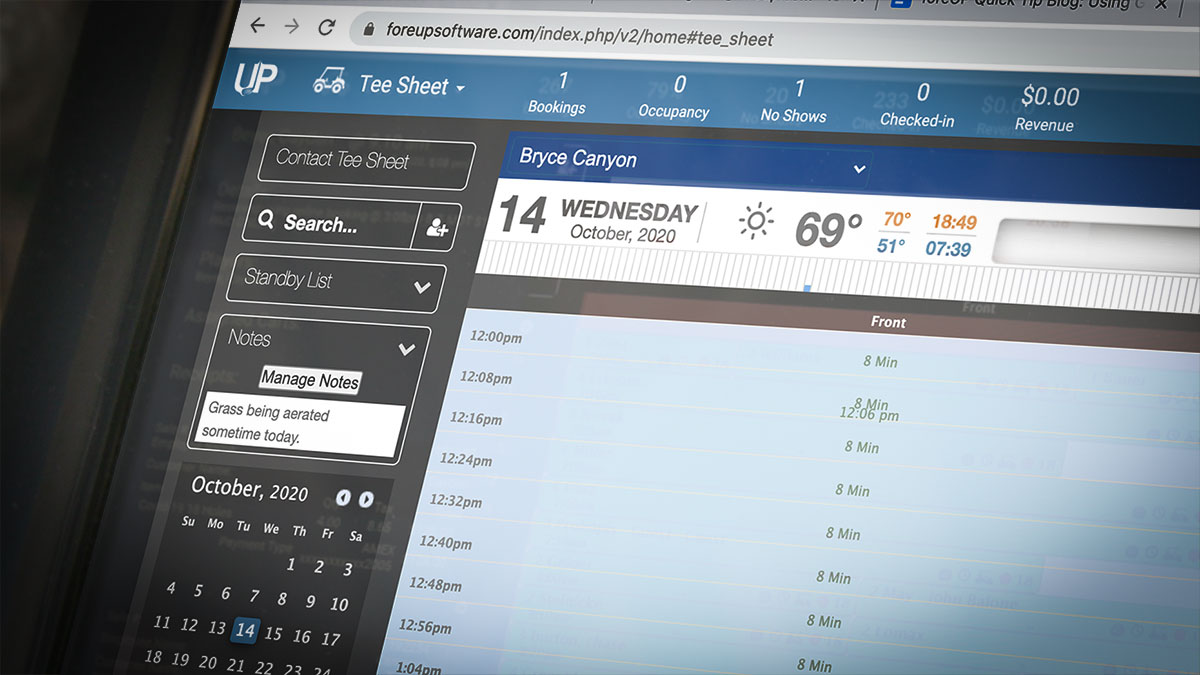

Like many head professionals across the country, Volk was forced to close his course in March due to the rapid spread of coronavirus. He and his team spent the downtime sterilizing common areas, creating new cleaning regimens for carts and other high-touch surfaces, and instituting social distancing protocols throughout the facility. They also made modifications to payment policies that are already paying dividends.

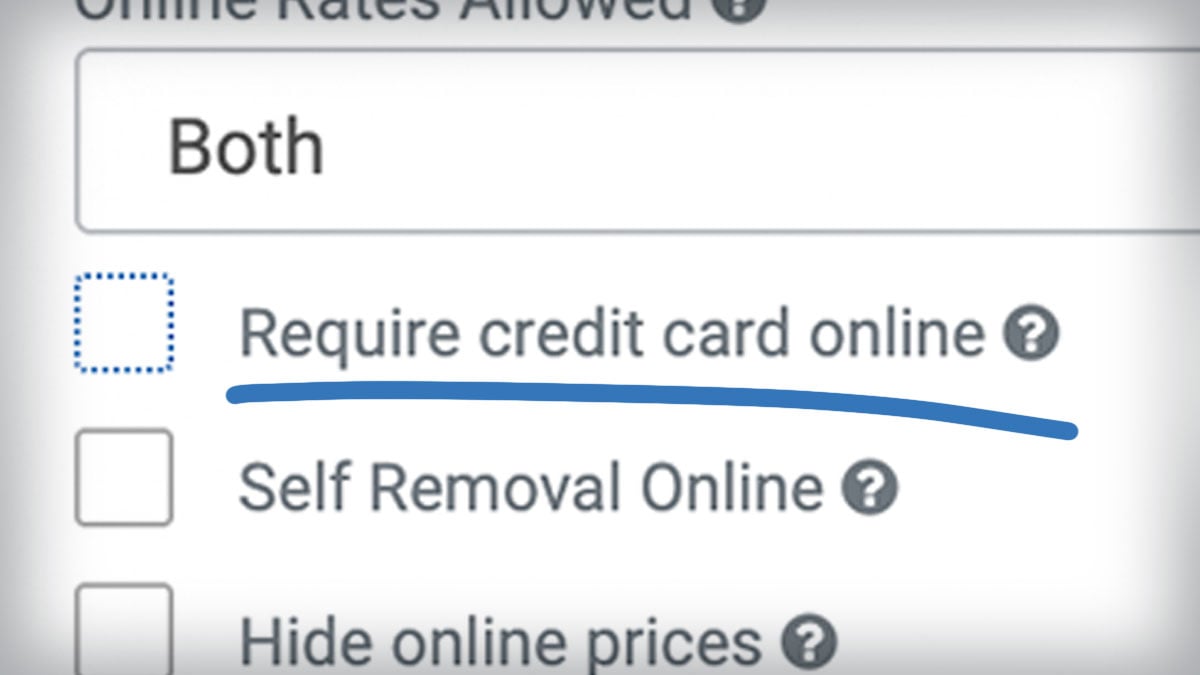

Utilizing the club’s POS system and tee time software, Volk created a host of procedures to facilitate touch-free check-in and reduce face-to-face interactions between staff and golfers on and off the course. He took the added—and some might argue, risky—step of integrating new requirements that customers pay for the full price of their tee time when it’s booked, regardless of when, where or by whom the reservation is made.

With the simple click of an on-screen button, Volk and his staff solved the age-old problem of revenue lost to cancellations and no-shows that has haunted so many of his colleagues.

A Strategy Whose Time has Come

To be fair, a considerable amount of thought and planning went into moving to prepayments at Valley View; however, the transition ran smoothly, and Volk’s calculated gamble generated returns almost immediately.

Weekly course occupancy quickly began to surpass previous years’ numbers. Despite having to increase tee times intervals from nine to 10 minutes in order to meet COVID guidelines, Valley View broke rounds played records each month from April through July, with the course hosting 13,000 rounds in July alone. Somewhat surprisingly, pro shop sales also increased monthly during the same period.

Perhaps it was a product of the upheaval taking place outside the natural confines of the course, but golfers—including those who would have previously balked at having to pay for their greens fees before arriving to play—accepted the policy changes without issue. No-shows disappeared, players arrived on time for their rounds, and pace of play improved. Better still, overall customer satisfaction increased.

With data to support his claim, Volk is convinced that prepayment is the best strategy moving forward, not only for Valley View but for public and semi-private operators across the country. That’s why, pandemic or not, he doesn’t plan to ever return to his former booking practices. Doing so, he contends, would be tantamount to going backwards.

History suggests that some will join Volk in a payment revolution, while others will remain loyal to less “radical” collection approaches. Be that as it may, the industry as a whole would do well to heed the words of an anonymous sage who once quipped, “Innovation is progress in the face of tradition,” and fight the tendency to remain so enthralled by the past that it forsakes the future.